The model industrial town of Pullman, Illinois had its beginning on May 26, 1880. This town was the physical expression of an idea born and nurtured in the mind of George M. Pullman (1831–1897), president of Pullman’s Palace Car Company.

By developing a total environment, superior to that available to the working class elsewhere, Pullman hoped to attract the most skilled workers to build his luxury rail cars, and to attain greater productivity as a result of the better health and spirit of his employees. He hired architect Solon S. Beman (1853-1914), landscape architect Nathan F. Barrett (1845–1919) and civil engineer, Benzette Williams (1844–1917), to help him realize his vision.

The 4,000-acre tract selected for the factory and town lay in the open prairie and marsh land along the western shore of Lake Calumet, approximately 13 miles south of Chicago. The town would have accessibility to the big city markets and railroad connections throughout the entire country. It was linked to Chicago and the southern states by the Illinois Central Railroad and to the world by Lake Calumet’s connection to Lake Michigan and the St. Lawrence River.

Construction of the town was executed by Pullman employees. Structures were made of brick, fashioned from clay found in Lake Calumet. A brickyard was built south of the town for this purpose. Pullman shops produced component parts used throughout the building of the town. This project was one of the first applications of industrial technology and mass production in the construction of a large-scale housing development. The town of more than 1,000 homes and public buildings was completed by 1884.

Each dwelling was provided with gas and water, access to complete sanitary facilities, and abundant quantities of sunlight and fresh air. Front and back yards provided personal green space, while expansive parks and open lands provided larger, shared ones. Maintenance of the residences was included in the rental prices, as was daily garbage pickup.

Learn more about Pullman’s structures:

The Strike of 1894

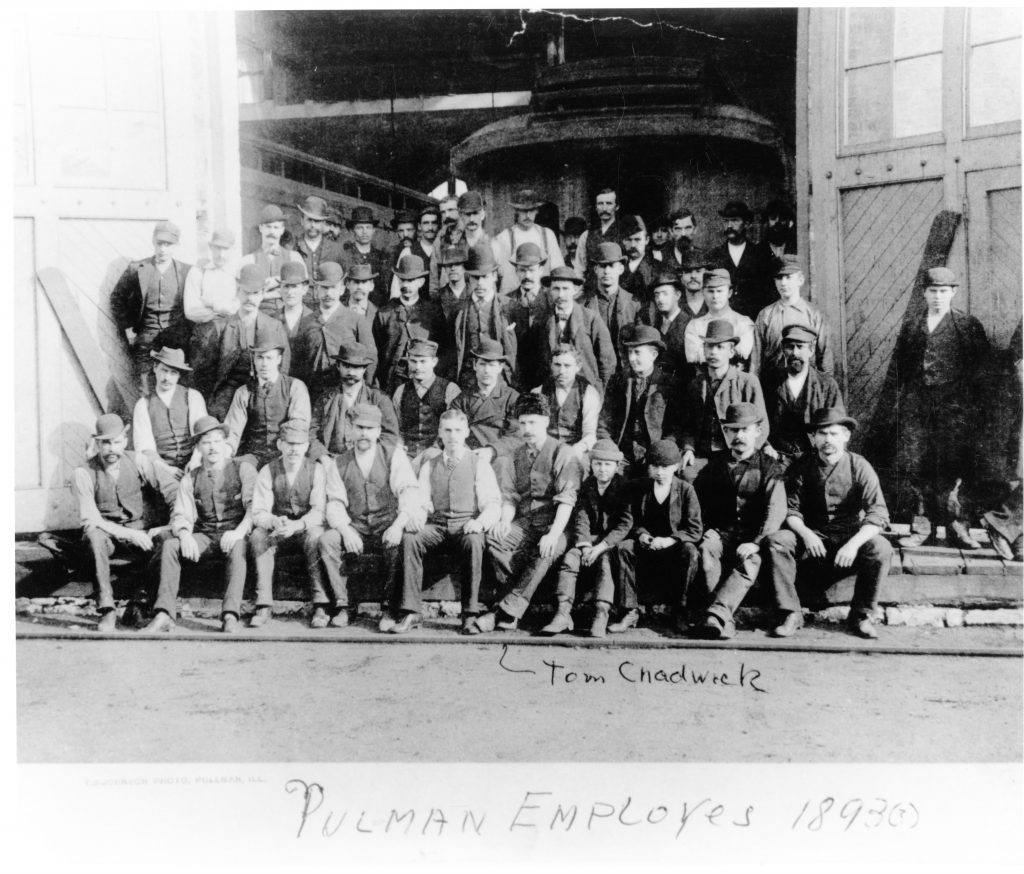

In 1893, an economic depression hit the country. In response to a drop in orders for rail cars, the company lowered its workers’ wages but not the rents it charged those workers for company housing. When a delegation of workers tried to meet with Pullman to present their grievances, he refused to meet with them and ordered them fired. The delegation then voted to strike, and Pullman workers walked off the job on May 11, 1894.

By June 27, the American Railway Union joined the Pullman strikers in solidarity. The strike grew into one of American history’s largest labor actions, paralyzing most of the railroads west of Detroit and threatening the national economy. The strike ended violently by mid-July when President Cleveland intervened with Federal troops.

In 1898, the Illinois Supreme Court ordered the Pullman company to sell all non-industrial land holdings in the town, but the company did not comply until 1907.

Pullman Today

Today, Pullman is a strong, historic community, committed to preserving its heritage.

In 1960, the area was threatened with demolition for the construction of an industrial park near the newly built Lake Calumet shipping port. Knowledgeable and well-versed on the history of their community, residents organized to save the factory and their neighborhood. Residents successfully halted the construction of the industrial park. The Pullman Civic Organization (PCO) emerged from this success.

A small group of residents formed the PCO’s Beman Committee to focus on the preservation of the architecture of the original town. Through their efforts, the Town of Pullman was designated an Illinois Historic District in 1969, a National Historic Landmark in 1970, and in 1972, the area south of the factory was designated as one of the first landmark districts by the City of Chicago. The North Pullman Historic District was created in 1993.

The Historic Pullman Foundation (HPF) was formed in 1973 with a mission to expand the preservation efforts and to seek greater resources from outside the community.

In 1975, when the Hotel Florence and all of its original furniture and fixtures were in jeopardy of being sold at auction, the HPF took action and, with the help of George Pullman’s granddaughter, Florence Lowden Miller, was able to purchase the hotel and all of its contents. For the next 25 years, the HPF worked to restore the building and keep it open to the public. The foundation also acquired several of the town’s other architectural gems: Market Hall and the Historic Pullman Center (renamed the Florence Lowden Miller building). The HPF’s visitor center is located in a newer structure that sits on the site of the original Arcade Building.

In 1991, the State of Illinois purchased the Hotel Florence and Pullman Factory Clock Tower and Administration buildings under the auspices of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency (IHPA) for the development of the Pullman State Historic Site. The Pullman Factory Clock Tower eventually was transferred to the National Park Service. Both sites have undergone extensive preservation and restoration work.

The Pullman district benefits from its diverse and proud population. Some residents come to Pullman with an interest in its history. Some come with a passion for preservation and a desire to renovate their own home. Some are longtime residents, with roots in Pullman that go back generations. All appreciate and share a deep sense of community.

1894

Pullman Strike occurs after George Pullman refuses to meet with a committee of workers to discuss grievances. Eugene Debs’ American Railway Union becomes involved by boycotting Pullman cars, refusing to move them on the rails. With rail service interrupted and the U.S. mail disrupted, the situation escalated to a national level as Federal troops were brought in to end the strike.